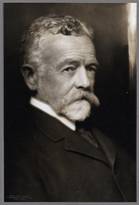

Henry

Cabot Lodge: The League of Nations Must Be Revised (Aug. 1919)

[From Congressional

Record, 66th Cong., 1st sess., 1919, 3779-84.]

. . . All the great energy and power of the Republic

were put at the service of the good cause. We have not been ungenerous. We have

been devoted to the cause of freedom, humanity, and civilization everywhere. Now we are asked, in the making

of peace, to sacrifice our sovereignty in important respects, to involve

ourselves almost without limit in the affairs of other nations and to yield up

policies and rights which we have maintained throughout our history. We are

asked to incur liabilities to an unlimited extent and furnish assets at the

same time which no man can measure. I think it is not only our right but our

duty to determine how far we shall go. Not only must we look carefully to see

where we are being led into endless disputes and entanglements, but we must not

forget that we have in this country millions of people of foreign birth and

parentage.

Our one great object is to make all these people

Americans so that we may call on them to place America first and serve America

as they have done in the war just closed. We can not Americanize them if we are

continually thrusting them back into the quarrels and difficulties of the

countries from which they came to us. . . . We shall have a large portion of

our people voting not on American questions and not on what concerns the United

States but dividing on issues which concern foreign countries alone. That is an

unwholesome and perilous condition to force upon this country. We must avoid

it. We ought to reduce to the lowest possible point the foreign questions in which we involve ourselves. . . . It will all

tend to delay the Americanization of our great population, and it is more

important not only to the United States but to the peace of the world to make

all these people good Americans than it is to determine that some piece of

territory should belong to one European country rather than to another. . . .

In what I have already

said about other nations putting us into war I have covered one point of

sovereignty which ought never to be yielded—the power to send American soldiers

and sailors everywhere, which ought never to be taken from the American people

or impaired in the slightest degree. Let us beware how we palter with our

independence. We

have not reached the great position from which we were able to come down into

the field of battle and help to save the world from tyranny by being guided by

others. Our vast power has all been built up and gathered together by ourselves

alone. We forced our way upward from the days of the Revolution, through a

world often hostile and always indifferent. We owe no debt to anyone except to

France in that Revolution, and those policies and those rights on which our

power has been founded should never be lessened or weakened. It will be no

service to the world to do so and it will be of intolerable injury to the

United States. We will do our share. We are ready and anxious to help in all ways

to preserve the world's peace. But we can do it best by not crippling

ourselves. . . .

. . . I am thinking of what is best for the world, for if the United States

fails the best hopes of mankind fail with it. I have never had but one

allegiance—I can not divide it now. I have loved but one flag and I can not

share that devotion and give affection to the mongrel banner invented by a

league. Internationalism, illustrated by the Bolshevik and by the man to

whom all countries are alike provided they can make money out of them, is to me

repulsive. National I must remain, and in that way I like all other Americans

can render the amplest service to the world. The United States is the world's best hope, but if you

fetter her in the interests and quarrels of other nations, if you tangle her in

the intrigues of Europe, you will destroy her power for good and endanger her

very existence. . . .

No doubt many excellent and patriotic people see a

coming fulfillment of noble ideals in the word "League for Peace." We

all respect and share these aspirations and desires, but some of us see no

hope, but rather defeat, for them in this murky covenant. For we, too, have our ideals, even if we differ from those who

have tried to establish a monopoly of idealism. Out first ideal is our country,

and we see her in the future, as in the past, giving service to all her people

and to the world. Our ideal of the future is that she should continue to render

that service of her own free will. She has great problems of her own to solve,

very grim and perilous problems, and a right solution, if we can attain to it,

would largely benefit mankind. We would have our country strong to resist a

peril from the West, as she has flung back the German menace from the East. We

would not have our politics distracted and embittered by the dissensions of

other lands. We would not have our country's vigor exhausted, or her moral

force abated, by everlasting meddling and muddling in every quarrel, great and

small, which afflicts the world. Our ideal is to make her ever stronger and

better and finer because in that way alone, as we believe, can she be of the greatest service to the world's peace and to the

welfare of mankind.